¡Ay, Ramón! ¿Qué hacer con el jamón?: the pronunciation of the N.

apologize for the alteration I made to the song lyrics, which I want to share with you, in the title of this post, but it amused me.

Ay, amor, ¿qué hacer con este amor? (Oh, love, what to do with this love?)

Ay, Ramón, ¿qué hacer con el jamón? (Oh, Ramón, what to do with the ham?)

They sound similar, don’t they? Sorry for the bad joke. The point is, this post needs sound because we’ll be talking about the pronunciation of the letter n in Spanish, which, while it doesn’t have too many variations, does have a few. So I thought of leaving you the following video so that, if you want, you can read along with music. It’s also because it contains many examples of the velar pronunciation of n at the end of words, something that doesn’t occur in my variety of Spanish, but which I personally love the sound of. I’ll also be using technical terms and symbols from the International Phonetic Alphabet, which might not mean much to some readers, but hearing the sounds makes everything easier.

So, here’s the video.

Vico C. 1 de Noviembre 2024. Lo grande que es perdonar. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_kzbd56qpf8

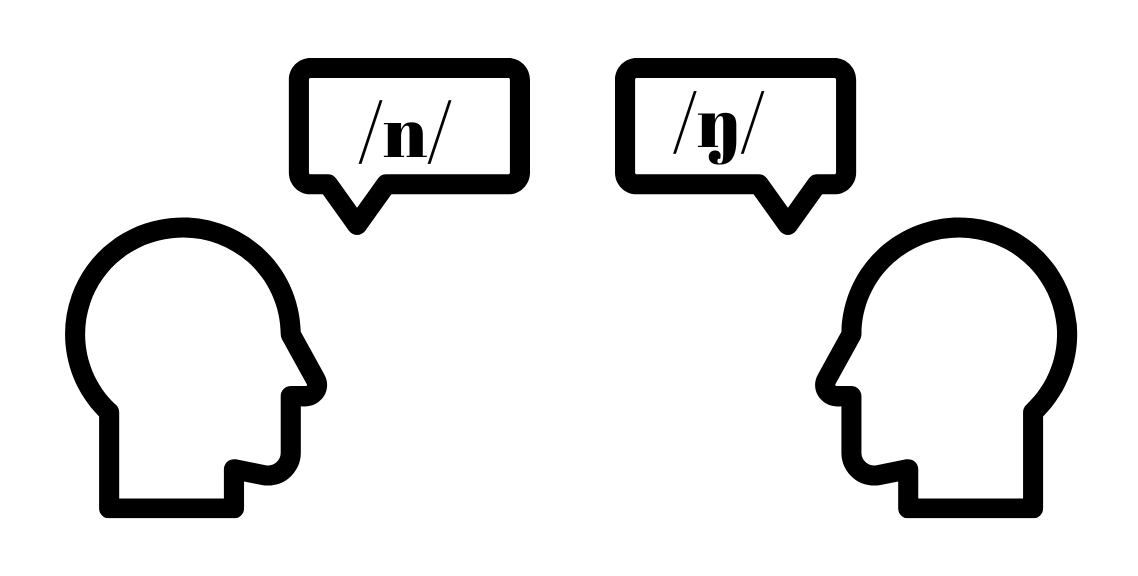

The letter n is part of the nasal sounds in Spanish, which are sounds—not exclusive to Spanish—that are produced with the soft palate lowered, allowing air to flow through the nose. From a phonetic perspective, n is a voiced nasal consonant, and its point of articulation can basically be either alveolar, meaning the tongue tip rests against those small ridges behind the upper teeth, or velar, where the back of the tongue presses against the back of the hard palate. I say “basically” because there are nuances: the point of articulation depends on the consonant sounds that follow it and, of course, the specific variety of Spanish being spoken. It’s worth noting that if the n is followed by a vowel, its pronunciation will always be the most common: voiced alveolar nasal.

La pronunciación más frecuente de la letra N es la nasal sonora alveolar /n/. The most common pronunciation of the letter n is the voiced alveolar nasal /n/. In fact, nearly all the ns in the previous sentence are pronounced this way except, as we’ll see next, the n in “frecuente” (frequent), where the point of articulation changes. This is because the point of articulation for n changes according to the consonant that follows it. For instance, before /t/ it is dental, meaning the point of articulation is the upper incisors, as in “frecuente” (frequent), while before /b/ it becomes bilabial, as in “son buenos” (they are good) when both words are pronounced without a pause in between. In this case, it almost sounds like an m. And I have to use separate words here because in Spanish, there is a spelling rule that prevents the letter n from being followed by a b within a single word. Another example is when it appears before f, where the point of articulation becomes labiodental, adapting to the articulation of the consonant that follows.

Before /k/ and /g/, the n becomes a voiced velar nasal consonant (/ŋ/). This means that, since these consonants have a velar point of articulation, the n preceding them adjusts its point of articulation, just as in the cases we mentioned in the previous paragraph, though this time it shifts further from its most common point of articulation. In words like tango (tango), ángel (angel), ancla (anchor), or banco (bank), the n is pronounced as a voiced velar nasal consonant, meaning the back of the tongue rests against the rearmost part of the hard palate. Once again, when n is followed by a consonant, it adapts its point of articulation to match that of the following consonant. It’s worth noting that if the order of sounds is reversed, the n reverts to its alveolar articulation, as in words like técnica (technique), arácnido (arachnid), asignar (to assign), or magnate (tycoon).

A very common variation in the pronunciation of n is the velar pronunciation at the end of a word, especially if it’s the last word spoken or if the following word begins with a vowel. This variant is widespread – in the Caribbean, along the Pacific coast, and so on. This pronunciation creates a musicality unfamiliar to my variety of Spanish, but one that I personally love the sound of. Let’s look at a few examples.

No me mates más co/n/ ese rencor…

No me mates más co/ŋ/ ese rencor…

¡Ay, Ramón! ¿Qué hacer co/n/ el jamón?

¡Ay, Ramón! ¿Qué hacer co/ŋ/ el jamón?

I apologize for my complete lack of singing talent. That’s precisely why I brought you the song – to keep my audio contribution to this post to the bare minimum. But, have you noticed the difference? Which pronunciation do you prefer in these cases? Below, I’ve included the lyrics to the song so you can read along as you listen, with the ns represented in phonetic symbols. You’ll notice that some ns aren’t replaced by phonetic symbols. This is for two reasons: first, there’s the phenomenon of n reduction, meaning in some cases, especially at the end of a word, the sound is very subtle and almost unarticulated. Second, in other cases – even after listening to this song around 500 times to write this post – I’m still unsure how the sound was articulated in certain words. Yes, native speakers of a language sometimes have questions about our own language and don’t always understand everything. Thanks for reading, and enjoy the music!

Lo grande que es perdonar. Vico C con Gilberto Santa Rosa.

Vico C

Sé que te hice mil heridas

Casi imposibles de sa/n/ar

Y /n/adie ga/n/a la partida

Pues tú aquí y yo acá

Gilberto

Cua/n/do el orgullo /n/o te deja

E/n/trar e/n/ tiempo y e/n/ razón

Hay que callar todas sus quejas

Y hacerle caso al corazón

Vico C

¿Por qué llorar? ¿Por qué vivir así?

Gilberto

¿Por qué pe/n/sar para volver a mí?

Vico C

¿Qué importa ya? ¿Qué tie/n/e/ŋ/ que decir?

Ambos

Si vi/n/e ya, vi/n/e por tí, sólo por tí, ay amor

Vico C

/N/o me mates más co/ŋ/ ese re/ŋ/cor,

/n/o me tires más co/n/ la soledad,

/n/o hagas alia/n/zas co/ŋ/ el dolor,

/n/o empeores mi realidad.

Gilberto

Te doy hasta la lu/n/a co/n/ su esple/n/dor,

te doy hasta mi sa/ŋ/gre por tu piedad,

doy lo que sea para que tu corazón

mire lo gra/n/de que es perdo/n/ar.

Vico C

Y /n/o me mates más co/ŋ/ ese re/ŋ/cor,

y /n/o me tires más co/n/ la soledad,

y /n/o hagas alia/n/zas co/ŋ/ el dolor,

/n/o empeores mi realidad.

Gilberto

Te doy hasta la lu/n/a co/n/ su esple/n/dor, (Oye)

te doy hasta mi sa/ŋ/gre por tu piedad,

doy lo que sea para que tu corazón

mire lo gra/n/de que es perdo/n/ar,

Vico C

doy lo que sea para que tu corazón

Ambos

mire lo gra/n/de que es perdo/n/ar.

Vico C

/Nah/, /nah/, /nah/, /nah/

Gilberto

¿Qué vas a hacer e/n/ /n/uestra esquina

al realizar* que ya /n/o estoy?

¿Qué vas a hacer co/n/ esta ruina?

Si tú /n/o estás, /n/o sé quié/ŋ/ soy

Vico C

Si ya /n/o duermes e/n/ la /n/oche,

si tu so/n/risa ya /n/o está,

si /n/ada deja/n/ los reproches

regresa y /n/o mires atrás.

Gilberto

¿Por qué llorar? ¿Por qué vivir así?

Vico C

¿Por qué pe/ŋ/sar para volver a mí?

Gilberto

¿Qué importa ya, que tiene/ŋ/ que decir?

Ambos

Si vi/n/e ya, vi/n/e por tí, sólo por tí, ay amor.

Gilberto

/N/o me mates más co/n/ ese re/ŋ/cor,

/n/o me tires más co/n/ la soledad,

/n/o hagas alia/n/zas co/n/ el dolor,

/n/o empeores mi realidad.

Vico C

Yo te doy hasta la lu/n/a con su esplendor,

te doy hasta mi sa/ŋ/gre por tu piedad,

doy lo que sea para que tu corazón

mire lo gra/n/de que es perdo/n/ar.

Y /n/o me mates más co/ŋ/ ese re/ŋ/cor,

y /n/o me tires más co/n/ la soledad, (co/n/ la soledad)

y /n/o hagas alianzas co/ŋ/ el dolor,

/n/o empeores mi realidad.

Gilberto

Yo te doy hasta la lu/n/a con su esple/n/dor, (Oye)

te doy hasta mi sa/ŋ/gre por tu piedad,

doy lo que sea para que tu corazón

mire lo gra/n/de que es perdo/n/ar.

Vico C

Doy lo que sea para que tu corazón

mire lo grande que es perdo/n/ar.

Amor, ¿Qué hacer co/ŋ/ este amor?

(Hay heridas imposibles de sa/n/ar, la llegada a la partida)

/N/o sé quien soy

(¿Por qué llorar? ¿Por qué sufrir así? )

Me mata este dolor

(Si hoy vi/n/e por ti)

A decirte regresa y /n/o mires atrás

(Amor, ¿Qué hacer co/n/ este amor?)

No, no, no empeores la realidad!

(/N/o sé quien soy)

Te doy mi vida, te doy mi sa/ŋ/gre

(Me mata este dolor)

Yo, yo aún te ve/n/ero

Ay, amor, ¿Qué hacer co/ŋ/ este amor?

(¿Qué vas a hacer al realizar que ya /n/o estoy ya aquí?)

/N/o sé quien soy

(Si ya /n/o duermes en las /n/oches, /n/ada dejan los reproches, corazón?)

Me mata este dolor

(Regresa a mí)

Yo te doy hasta la lu/n/a

(Amor, ¿Qué hacer con este amor?)

Yo, mi vida entera

(/N/o sé quie/n/ soy)

Como tú no hay /n/i/n/gu/n/a

/N/o mires atrás

Vico C, born to a Puerto Rican family, was born in the United States and moved to Puerto Rico with his family when he was five. Gilberto Santa Rosa, on the other hand, is Puerto Rican. Despite sharing the same linguistic roots, if you read and listen carefully, you’ll notice that, in some cases, the same n is pronounced as /ŋ/ by Vico and as /n/ by Gilberto.

Realizar: In Spanish, the verb realizar means to carry out or accomplish something specific. However, in some varieties of Spanish with strong English influence, such as Caribbean Spanish, this verb is used as a synonym for darse cuenta (to realize), due to a transfer from the English verb “to realize.”

Leave a Reply