¿Esta es tu casa? Possesives in Spanish

ossessives are words that indicate to whom or to what something belongs. They agree with the possessed noun, not the possessor, in grammatical gender and number, and there are two types: unstressed possessives (or possessive adjectives) and stressed possessives (or possessive pronouns). In this article, we’ll look at what they are and how to use them. Let’s go!

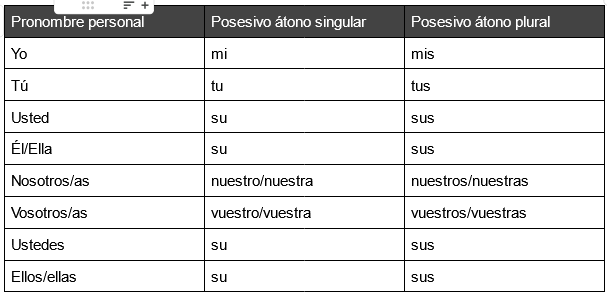

Posesivos átonos.

As shown in the table, only in the first-person plural (nosotros/as) and in the second-person informal plural (vosotros/as) are there forms of unstressed possessives for both masculine and feminine. So, let’s take a look at this first, as it is, at least, a short topic.

As we mentioned earlier, possessives agree in gender and number with the possessed noun, not with the possessor. For instance, nosotros can refer to a group made up exclusively of men, but we say nosotros amamos a nuestra madre (“we love our mother”) because madre is a grammatically feminine noun. Similarly, if we use nosotras, which refers to a group made up exclusively of women, we say nosotras amamos a nuestro padre (“we love our father”) because padre is a grammatically masculine noun.

In the case of number, possessives also agree with the possessed noun, not with the possessor. Let’s look at some examples.

Mis amigos vienen a cenar a mi casa. My friends are coming to have dinner at my house.

¿Dónde están tus llaves? ¿Y tu chaqueta? Where are your keys? And your jacket?

Hoy compré comida para mis gatos y mi perro. Today I bought food for my cats and my dog.

As seen in the examples, we use the possessive that agrees in number with the possessed noun.

The possessives su and sus can be ambiguous because, as shown in the table, they can refer to él, ella, usted, ellos, ellas, or ustedes. For greater clarity, if necessary, they can be replaced by a construction using the preposition de, another way to indicate possession in Spanish. This construction is formed with the possessed noun, the verb ser conjugated with it, the preposition de, and a personal pronoun or a name.

Este es su libro. Este es el libro de ella/él/ustedes. This is her/his/your book.

Estos son sus libros. Estos libros son de María. These are her books.

Regarding their position in the sentence, they always precede the noun they refer to. As we’ve seen in other articles, word order in Spanish is quite flexible, allowing emphasis on one element or another. When we change the word order in a sentence containing unstressed possessives, they maintain their position before the noun.

Este es su libro. Su libro es este. This is his/her/your/their book.

Estos son sus libros. Sus libros son estos.

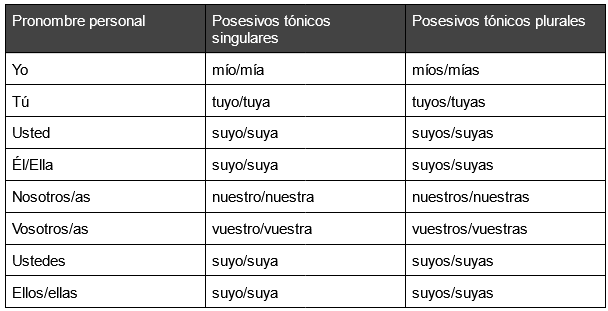

Posesivos tónicos.

The stressed possessives are pronouns because they can replace the noun in the sentence. Just like the unstressed ones, they agree with the possessed noun in grammatical gender and number. Let’s take a look at which ones they are and some examples of their use, which is somewhat more complex than that of unstressed possessives since, in this case, all of them have both a masculine and a feminine form.

Let’s look at examples of the use of stressed possessives and, next, a bit of linguistic pragmatics: when does someone choose to use one or the other? Stressed possessives, like unstressed ones, agree in grammatical gender and number with the noun they are related to. Additionally, they can replace the noun, meaning the noun doesn’t have to be mentioned in the sentence.

¿De quién es esta camisa? Whose shirt is this?

Esa camisa es mía. Es mía. That shirt is mine. It’s mine.

¿Estos zapatos son tuyos? Are these shoes yours?

Sí, esos zapatos son míos. Sí, son míos. Yes, those shoes are mine. Yes, they’re mine.

¿Estos cafés son vuestros? Are these coffees yours?

Sí, esos cafés son nuestros. Sí, son nuestros. Yes, those coffees are ours. Yes, they’re ours.

Again, the order of the sentence can be changed to emphasize different things.

Esos son nuestros cafés: this emphasizes that the coffees belong to us rather than to other groups of people. Esos cafés son nuestros: this emphasizes that these particular coffees belong to us, rather than other coffees. Of course, there will be reasons that lead us to use one option or the other. In the first case, for example, it could be that we had been waiting for the coffees before anyone else, and in the second case, that these particular coffees are of the specialty we ordered.

Stressed pronouns can also be used together with the corresponding definite article to emphasize the possession of a specific noun. The definite article is always placed before the stressed pronoun in the sentence. Let’s see some examples.

Esa camisa es la mía. Esa camisa es la mía.

Esos libros son los tuyos. This books are yours.

If the context allows, we can omit the noun.

Los nuestros son los verdes. Ours are green.

Las suyas son esas. Again, since suyo and its variants can be ambiguous, they are often replaced by the construction with de: las suyas son esas, las de él/ella, etc., son esas.

A bit of linguistic pragmatics.

Use of unstressed possessives: emphasis on the noun or on the action.

Unstressed possessives (mi, tu, su, etc.) are used when the speaker wants to give more relevance to the noun than to the act of possession. This happens because unstressed possessives have a more neutral character and blend into the natural flow of the sentence without overly highlighting the relationship of ownership.

Typical contexts of use:

New information: When the noun is more relevant than the possessive relationship. Example: “Mira mi libro.” (“Look at my book.”) (The focus is on the book as the relevant object).

Everyday contexts: When the possessive relationship is expected or does not require additional emphasis. Example: “Voy a buscar mis gafas.” (“I’m going to look for my glasses.”) (The possession is secondary to the purpose of the action).

Clarity and linguistic economy: Unstressed possessives are shorter and more efficient in situations where possession does not need to be highlighted.

Use of stressed possessives: emphasis on the possession relationship.

Stressed possessives (mío, tuyo, suyo, etc.) are used when the speaker wants to highlight, contrast, or emphasize the relationship of ownership. They are pragmatically marked and usually appear in contexts where the focus is on who owns the object or in comparison with other possible owners.

Typical contexts of use:

Emphasis on possession: Example: “Ese coche no es tuyo; es mío.” (“That car is not yours; it’s mine.”) (The focus is on who owns the car).

Contrast: When an opposition is made with another possession. Example: “El éxito no fue de ellos, fue nuestro.” (“The success was not theirs, it was ours.”)

Reaffirmation: To emphasize the ownership of something, especially in emotional or argumentative contexts. Example: “Esta casa es mía, no lo olvides.” (“This house is mine, don’t forget it.”)

Elliptical responses: When the noun is omitted and the possessive is used as a pronoun. Example: “¿Es este tu abrigo? No, el mío es más grande.” (“Is this your coat? No, mine is bigger.”)

Other pragmatic factors.

Social context and formality:

In more formal contexts, speakers tend to prefer less marked constructions (unstressed possessives) to maintain a neutral tone. Stressed possessives, being emphatic, can sound more emotional or informal depending on the context.

Formal example: “Por favor, revise sus documentos.” (“Please review your documents.”) Informal or emotional example: “¡Esos documentos son míos!” (“Those documents are mine!”)

Economy of discourse:

Speakers opt for stressed possessives instead of longer constructions when the noun is already implied or known.

Ejemplo: “¿De quién es este cuaderno? Es mío.” Who’s notebook is this? It’s mine.

Communicative intention:

The choice also depends on the speaker’s intent to highlight the emotional relationship with the object or with the interlocutor.

Neutro: “Es mi casa.” It’s my house.

Enfático: “¡Es mía!” It’s mine!

Finally, as we saw earlier, the use of stressed possessives with definite articles is the option chosen when the speaker wants to make it clear that a specific noun is involved in the possession relationship, leaving no room for it to be another one.

As a language learner, I know very well that this topic, especially at the beginning of learning, can be a bit complex. The good thing is that, despite the complexity, it is something that is used very frequently, so the opportunities to encounter possessives in real language samples and to have to use them in both spoken and written language are also very frequent, which helps us internalize our knowledge relatively quickly. Thank you for reading, and if you have any questions, feel free to write to me.

Leave a Reply