No me hagas pirar porque piro: Why is it worth learning colloquial expressions in our target languages?

y first contact with foreign languages was when I was eight or nine years old, when I started learning English. We're talking about a few years ago, in a small town in the northwest of Uruguay, in the pre-Internet era. The English I was learning at that time, although it was for children and later for teenagers, was the academic institutional kind of English.

I think this is something that has happened to all of us who learn a foreign language, especially those of us who learn it in an institution: we learn one thing, but then we are exposed to the language spoken on the street and find something quite different, even things that we simply cannot understand, regardless of the level of linguistic competence we have acquired. Because, always from my point of view and as I mentioned in this article, one speaks the way people speak, and “the way people speak” has many definitions. That is, most of us change the way we speak in many cases, depending on the interlocutor, the communicative situation, etc. The point is that I, there, in the northwest of Uruguay, at a time when there was no Internet and only three television channels, started to come into contact with real English about ten years after I had begun learning it, and I realized that there were many things I did not understand.

Then I started traveling, and through my travels, I realized how much easier a trip becomes when you speak the language of the country you are visiting. And not just in the obvious way. Clearly, if you master the local language of a country, communication will be much easier than if you speak a foreign language that your interlocutor does not speak – or does not want to speak, even if they know it, which happens in some countries. Still, beyond linguistic competence, being able to speak at least a little of the language of the country we visit already makes a big difference. In general, locals appreciate it when we at least try to say a few words in their language. From my point of view, it’s a sign of respect: we all know how difficult it is to learn foreign languages, but when we can say even a little, we show that we have made at least some effort to connect with the culture of the country we are visiting. People appreciate it, I promise, even if we only know a few words. For example, I know how to say, “Hello, I am Federico” (Përshëndetje, unë jam Federico) in Albanian and “Hello, how are you?” (Zdravo, kako si?) in Serbo-Croatian. I don’t know how to say anything else in either language, but the times I have been able to use these phrases with native speakers, the reactions were very positive. And these are just common phrases!

As an adult, I began learning German and French, improving my English, and decided to pursue a master’s degree in Spanish as a foreign language. Basically, this was a consequence of my travels and the cultural exchange they involved. One day, I was taking a C1-level German course in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. I don’t remember exactly what we were talking about, but our teacher – a native German – said something to us with his strong German accent and a smirk on his face, because I think he knew exactly what reaction he was going to provoke. He told us this:

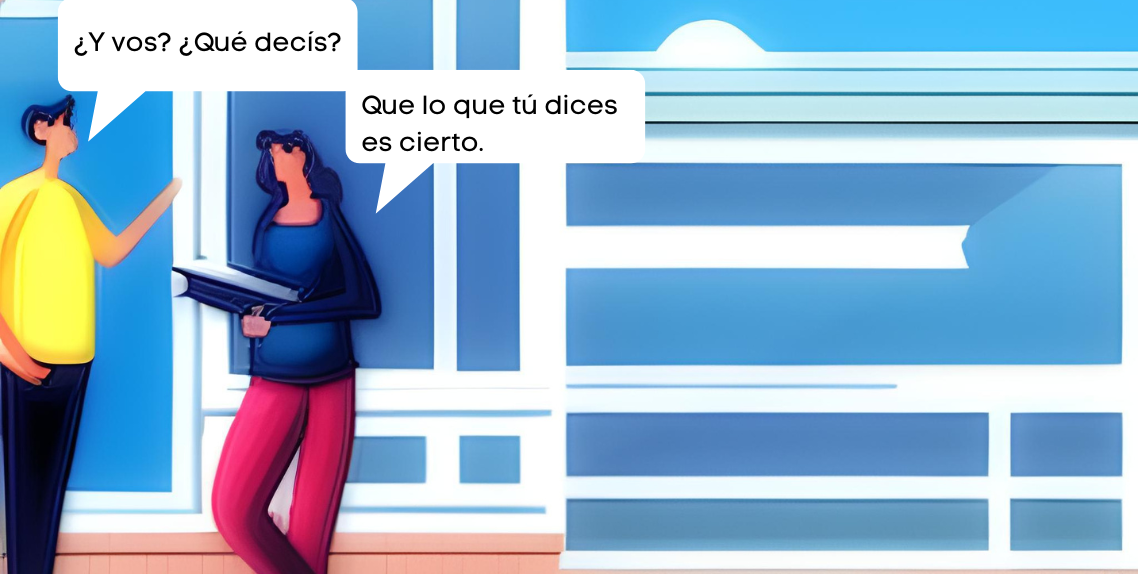

– Cuándo salgamos de este quilombo…

The whole group burst into laughter. The word quilombo, which is frequently used in Rioplatense Spanish, comes from Portuguese, a language that has strongly influenced our Spanish. During the time of slavery, quilombos were places where escaped slaves lived. This word, in turn, originates from Kimbundu, a language spoken in Angola. Today, quilombo has lost its original meaning and, among other definitions, it means problem or mess in our region. In fact, it is even recognized by the RAE. But the reason we laughed was that we didn’t expect our teacher to use that word, so characteristic of our part of the world. It was, of course, laughter of surprise and appreciation.

I know how to say three words in Albanian because a few years ago, I met someone from Albania. I always try to make contacts online to practice the languages I learn, and whenever someone reaches out to me, the first thing I focus on is verifying that the person behind the profile is real. That time, this person from Albania contacted me, and when we started talking, I told them I was from Uruguay. Since my country is relatively little known, I asked if they had any idea where it was.

– ¿Uruguay? ¡Claro que sé dónde queda, boludo!

I completely dropped my guard because it just threw me off. I never would have expected someone from Albania to call me boludo. This word has its origins in the wars of independence in Argentina, when the gauchos faced off against Spanish soldiers with the weapons they had, including the boleadoras, which are a type of thrown weapon made of two or three stone balls connected by leather straps. Those who carried the boleadoras were called boludos. However, the gauchos were very exposed to the gunfire from the Spanish, so they died easily. For this reason, an Argentine politician once said that one shouldn’t be boludo. This is where the first meaning of the word, fool or stupid, comes from. Today, the word boludo, which is used in Argentina and Uruguay, has many more meanings. In fact, its most frequent use today is as a vocative, as a way of calling someone, and in that context, it doesn’t carry any insulting meaning. And this person from Albania not only used that word but used it in a very natural way, just like I do all the time when speaking my variety of Spanish. So, it piqued my curiosity, and the communication flowed much more easily.

So, why am I telling all this? Simply because, from my point of view, it is very useful to learn colloquial expressions in the language or languages we are learning. And no, I’m not going to provide a list of these kinds of expressions in Spanish, as they are specific to each country. The message I want to convey here is that, no matter what language you are learning, try to get in touch with a local to exchange and learn things that you won’t learn from books, things that you probably won’t learn in a language school either, but that you will hear on the streets all the time. Because using these expressions will be something unexpected for the interlocutor and will generate a positive reaction, creating a sense of linguistic closeness, so to speak, and will make communication flow more easily even if our command of the language we are using is not optimal.

Leave a Reply